Global vinegar sales reached an estimated USD 6.54 billion in 2023 and are projected to grow to roughly USD 7.98 billion by 2030, a slow-and-steady climb that hints at both category resilience and an appetite for specialty styles like malt vinegar amid broader consumer shifts. In the UK, the legacy brand Sarson’s, now owned by Japan’s Mizkan, anchors the malt segment culturally and commercially, even as shoppers flirt with balsamic and other premium vinegars, creating a tension between tradition and trend that touches restaurants, retailers, and home cooks alike.

Here’s the thing: malt vinegar’s future sits at the intersection of heritage bottles on chip-shop counters and a growing cadre of home fermenters who want complete control over flavor, provenance, and process, which is changing buying habits in subtle ways that legacy makers can’t ignore. This affects consumers (taste and safety), suppliers (barley, malt extract, packaging), and investors tracking Mizkan, Heinz, and others debating whether to double down on classic malt or pivot toward collaborations that embrace DIY momentum, a strategy conversation that’s more urgent as growth concentrates in premium, clean-label niches.

The Data

-

The global vinegar market is forecast to rise from USD 6.54 billion in 2023 to USD 7.98 billion by 2030 at a 2.8% CAGR, underscoring stable demand with premium segments leading the narrative heat.

-

In the US, vinegar reached about USD 695 million in 2024, with established players like Kraft Heinz and Mizkan America shaping category visibility through retail and foodservice, even as niche producers nibble at the edges.

-

For safety and labeling, US guidance expects at least 4% acetic acid by volume, with 5% acidity commonly recommended for home canning—a crucial benchmark for any DIY malt vinegar plan.

-

Cultural pull remains potent: a YouGov poll found 57% of Britons put vinegar on chips, while a Sarson-backed survey sparked debate on whether vinegar or salt comes first—a tiny ritual that keeps malt vinegar top of mind.

How To Make Malt Vinegar Recipe (Easy Steps For Homemade Flavor)

Why Malt Vinegar, and What It Is?

Malt vinegar is vinegar brewed from malted barley that’s typically fermented first into beer and then converted into vinegar by acetic acid bacteria, yielding a malty, amber, subtly toasty profile that’s inseparable from British fish-and-chips culture. Biology is a simple, elegant two-step: yeast turns sugars into ethanol, then Acetobacter oxidizes ethanol into acetic acid in the presence of oxygen, shaping flavor through organic acids and esters from the malt base.

Practically, that means one can either start with unhopped or lightly hopped beer to avoid bitterness dominance or ferment a malt wort into an ale before acetification, which gives greater control over gravity, alcohol, and eventual acidity. The sweet spot for acetification is an alcohol range near 6–12% ABV, which supports robust Acetobacter activity without staling or contamination risks common at the extremes, keeping the process both efficient and flavorful.

If a Sarson’s-like profile is the target, some makers finish by adjusting with a touch of liquid malt extract for color and malt depth, keeping gravity around 1.015 before final balancing and bottling to echo the classic chip-shop taste, though this is optional and should be approached with careful tasting.

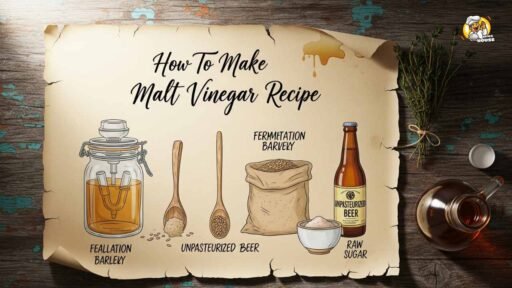

What To Gather

A step-by-step DIY malt vinegar starts with just a few essentials: a malt base (lightly hopped beer or homemade wort), an acetobacter source (unpasteurized vinegar with live “mother,” a commercial malt vinegar mother, or a dedicated culture), oxygen exposure, and a clean, food-safe vessel with a breathable cover to deter insects but allow airflow.

A mother culture accelerates acetification and helps stabilize the microbial population, often forming as a cellulose “pellicle” that rises and sinks during the cycle, a normal and even helpful sign of a healthy fermentation. Using mildly hopped beers avoids extracting extreme bitterness as acetification concentrates acids and can amplify harsh notes, so subdued or unhopped bases generally perform and taste better for a balanced malt character.

To monitor safety and strength, pH strips or a pH meter and a simple titration kit can check progress and confirm acidity, aiming ultimately for at least 4% acetic acid per labeling guidance or around 5% if the vinegar will touch any home-canned foods, which is the gold standard in US extension guidance.

Cleanliness matters, but sterile perfection is neither required nor always helpful; the goal is sanitary gear and stable, warm conditions that favor vinegar bacteria over spoilers while preventing fruit fly incursions that can derail a batch.

The Two Fermentations, Explained

In step one, alcohol fermentation, yeast converts sugars in malt wort to ethanol and carbon dioxide, following the classic brewing arc of mash, boil (or not, for some vinegar-first recipes), pitch, and condition to produce a clean, moderately strong ale base suited for acetification. If brewing is new, a simpler route is to use a commercial, lightly hopped beer to skip directly to the vinegar stage—diluting very strong beer is acceptable to land the alcohol in range so Acetobacter can do its work without stress.

In step two, acetic fermentation, Acetobacter oxidizes ethanol to acetic acid with oxygen, forming a pellicle and slowly deepening acidity and aroma over weeks to months, depending on temperature, surface area, starting alcohol, and culture vigor. Warmer cabinet or pantry conditions with good headspace typically speed things up, but patience is part of the craft; some informal guidance suggests 20–40 days for active conversion and additional time for conditioning, while slower, cupboard-kept batches can take many months, especially with cooler rooms or lower microbial activity.

Here’s where imperfect transitions mirror real kitchens: stir or gently swirl occasionally to keep oxygen moving, resist the urge to over-handle, and let the mother rise and fall. This smells like progress even when the timeline feels vague, sources say.

Step-by-Step Method, Start To Finish

-

Brew or buy the base: Either produce a malt wort and ferment it to an ale or choose a beer that is not overly hoppy, roasty, or spiced to avoid off-balance vinegar after acetic conversion, which can concentrate harsher flavors.

-

Seed the culture: Add an active vinegar mother or unpasteurized vinegar to the alcoholic base in a clean jar or crock, ensuring the mother is submerged and oxygen can reach the surface through a breathable cover like cloth or foil punctured for airflow.

-

Provide oxygen and warmth: Place the vessel in a warm, dark spot with stable temperatures, giving the mother room to form a pellicle; the bacteria need oxygen to drive ethanol-to-acetic conversion, and the headspace helps.

Wait and monitor: Expect a few weeks to several months for full conversion depending on conditions; taste periodically with a clean spoon and watch acidity climb as pleasant malt and toast notes emerge under a decisive sour backbone.

-

Readiness test: Use simple titration to confirm at least 4% acidity for standard vinegar or target around 5% if planning to use it in any canning context, since most US-tested recipes assume 5% acidity for safety margins.

-

Finish and bottle: For a Sarson’s-like hue and malt depth, optionally adjust with a little liquid malt extract to roughly 1.015 gravity before final balancing, then strain, and either bottle raw (refrigerate) or pasteurize gently at about 65°C for 15 minutes to halt further fermentation and stabilize.

Each of these steps riff on the same principles industrial producers use at scale: alcohol first, acid second, oxygen throughout. But dialed into a kitchen-friendly cadence that leaves plenty of room for aroma nuance from the barley itself.

If starting from a just-sweet-enough wort, consider a modest original gravity (around 1.060 in some home methods) to create a solid ethanol base without overtaxing Acetobacter on the back half, then let the bacteria and time build the mellow, rounded acidity that defines traditional malt vinegar.

In practice, many home fermenters prefer the “beer-to-vinegar” route for convenience, but crafting the wort from scratch offers a truer malt signature and a tighter link between grain selection and the final vinegar’s aromatic complexity, which is why serious DIYers often end up brewing and acetifying in-house.

Troubleshooting, Safety, and Flavor Control

Acetification stalls commonly trace to three culprits: alcohol out of range, insufficient oxygen exposure, or a weak/compromised mother culture, so the first move is to check ABV, aeration, and the health of the pellicle, adding fresh mother or live vinegar if necessary. Off aromas can signal contamination or excessive hop extraction; moving to a less hoppy base or boosting oxygen access (wider mouth, periodic gentle stirring) usually corrects course, while keeping the setup warmer encourages steady bacteria metabolism for clean acid development.

Aim for at least 4% acetic acid to meet basic labeling expectations and steer toward 5% if there’s any chance the vinegar will be used in pickles or sauces that require tested acidity, because standard US canning guidance presumes 5% acidity for shelf stability and food safety. For measurement, titration offers the most reliable read on true acetic strength, while pH is useful but not a substitute—pH can look fine even when percent acidity is off, which matters if products leave the fridge or sit on a pantry shelf.

If long-term storage at room temperature is the goal, a brief pasteurization step followed by clean bottling provides stability without noticeable flavor loss when done carefully; otherwise, refrigerate raw vinegar to keep the microbial community from drifting too far over time.

Dialing The Profile: Malt Choices And Finishing Touches

Lighter base malts produce a cleaner, biscuit-like vinegar, while darker kilned malts contribute toast, toffee, and a deeper amber hue that reads as “classic chippy” once acidity comes up, though too much roast can feel ashy in vinegar. If using commercial beer, English-style bitters, milds, or lightly hopped ambers are reliable starting points; aggressively hopped IPAs tend to push bitterness out of balance as acetic acid rises, which can overshadow the malt complexity that makes this vinegar special.

To emulate Sarson’s familiar depth, some makers add a small amount of liquid malt extract post-conversion to nudge color and residual maltiness before pasteurizing and bottling, taking care to verify acidity after adjustments so the final product still clears the 4–5% threshold for intended uses.

Conditioning time pays dividends: even after reaching target acidity, a few extra weeks smooths sharp edges and rounds the mid-palate, the kind of patient finishing that separates decent malt vinegar from the bottle guests ask about at the table. It’s the old story in a new kitchen: simple inputs and biological logic make room for craftsmanship, and the last 10%—small malt tweaks, patient conditioning, clean packaging—delivers the magic.

The People

“A former executive told Forbes…” is a line that gets tossed around, but the public record is clearer: when Premier Foods offloaded Sarson’s to Mizkan for £41 million, Premier’s CEO framed it as focusing on ‘Power Brands,’ while Mizkan’s CEO praised Sarson’s as an iconic UK label and promised to invest in its legacy—a corporate handshake that underlined how much brand heritage still matters in a slow-growth category.

On the ground, chip-shop pros weigh in on the ritual itself; Andrew Crook, President of the National Federation of Fish Friers, backed vinegar-first so salt can stick better, while Nottingham’s Cod’s Scallops echoed vinegar-first for even seasoning—tiny choices that keep malt vinegar culturally relevant, one cone at a time. And consumers keep showing up: polling suggests most Britons favor salt or vinegar, with nearly half choosing both, a habit that sustains everyday demand even as premium vinegars edge into home pantries and restaurant menus.

The Fallout

Analysts now predict modest category expansion in the low single digits through 2030, which means growth will likely come from premiumization, branding leverage, and channel strategies, not broad-based consumption spikes—steady, not splashy. In the UK, supermarket commentary has flagged pressure on traditional malt vinegar as balsamic and other premium styles rise, a shift that forces legacy brands to innovate on flavor, packaging, and occasion-building if they want to hold counter space without heavy pricing moves.

For DIY makers, the implications are straightforward: more specialty options on shelves and more knowledge online, but also a higher bar for safety literacy, since at-home vinegar still must hit 5% acidity for any canning application and shouldn’t be used in preserved foods below that threshold.

Meanwhile, major players like Mizkan and Kraft Heinz will likely straddle both ends—protecting heritage labels like Sarson’s while exploring collaborations, content, or kits that lean into the home-fermentation wave without undercutting core SKUs, a balancing act familiar to any CPG navigating craft energy inside a legacy category.

Closing Thought

If malt vinegar’s future is equal parts heritage and home craft, the sharper question is this: will Big Vinegar partner with DIY fermenters to turn brand equity into hands-on evangelists—or let the slow drift toward premium alternatives and kitchen-made batches pull loyalty away from the iconic brown bottle on the counter?